Patent Issues for Factory Automation Inventions in AI

January 15, 2021

Some of the most impressive AI breakthroughs are the result of separate contributions and heavy investments made by both large and small players in the tech-world. While many inventions in AI will be directed to cutting edge products, such as the in-home virtual assistant or the self-driving car, a lot of patentable innovations are directed to products which the public will never see or use, such as innovations in Factory Automation (FA).

Factory Automation components have many different features which are the subjects of numerous patent applications filed at the USPTO, such as “machine tools” (robotics, for example); controllers (servo controllers and programmable logic controller (PLC)); remote sensors; and data/parameter management techniques, just to name a few. Each of these features presents a unique set of challenges towards obtaining a patent, with some of these challenges being based on their very nature alone.

In particular, when the AI innovation is directed to an algorithm or a data collection technique, it risks receiving extra scrutiny by the USPTO. Ever since Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014), where the Supreme Court held that claims about a computer-implemented, electronic service for executing financial transactions cover abstract ideas ineligible for patent protection, a dramatic effect has been felt in the patent world on the validity of not only business method patents, but also software-based patents in nearly all fields of technology. In particular, patents directed to mathematical algorithms, methods of data collection and/or analysis, and methods replicating human activity are vulnerable for patent eligibility analysis in the USPTO. Unfortunately, these also happen to be some of the defining characteristics of AI and Factory Automation.

Following the seminal case of Alice, in cases where patent eligibility was raised at the district court level or the U.S. Court of Appeals of the Federal Circuit, a lopsided majority of all these cases were found to be non-patent eligible, especially at the Federal Circuit.

For example, two cases from the Federal Circuit which prove especially problematic for AI patent seekers is Electric Power Group, LLC v. Alstom S.A (2016) and Digitech Image Technologies vs. Electronics for Imaging (2014). Ironically, the cases themselves did not involve fact patterns specific to AI. However, they include language which, if applied broadly, targets inventions directed to data collection and analysis.

In Electric Power Group, the claims at issue require the reception of real-time data coming in from a wide geographical distribution; analyzing the data for instability that may be indicative of grid stress; displaying visualizations of the stability metrics; storing the data; and deriving a composite indicator of power grid reliability. What jumps out in this case is the manner in which the court took issue with an invention directed to gathering, analyzing, and displaying data. Notably, the court explained “[h]ere, the claims are clearly focused on the combination of those abstract-idea processes. The advance they purport to make is a process of gathering and analyzing information of a specified content, then displaying the results, and not any particular assertedly inventive technology for performing those functions. They are therefore directed to an abstract idea.” This statement can be, and has been, seized by examiners at the USPTO to reject claims which contain any form of “gathering and analyzing information of a specified content, then displaying results.”

In Digitech, the claims at issue were directed to the generation and use of an “improved device profile” that describes spatial and color properties of a device within a digital image processing system. Again, the facts of this case itself were not directed to AI, but the decision contains an extremely broad statement as follows: “The method in the ’415 patent claims an abstract idea because it describes a process of organizing information through mathematical correlations and is not tied to a specific structure or machine.”

Turning towards how these legal issues affect patents in Factory Automation. Consider the following two hypothetical categories of invention related to the improving the operation of a “machine tool” in a factory environment.

Category #1: A new structural feature

- Example: “Robotic arm with improved gripping mechanism.”

Category #2: A conventional structure with enhanced automation

- Example: “Robotic arm which automatically performs steps or corrects errors which previously required manual user-supervised control or user provided parameters.”

The first category of invention likely raises no issues on patentable subject matter under 35 U.S.C. §101, as the innovation is mechanical and structural in nature. However, the second category will likely receive extra scrutiny from the USPTO as attempting to implement “human activity” on a generic or conventional structure. The challenge for patent practitioners is to navigate decisions such as Electric Power Group and Digitech and avoid having the claim interpreted as mere data collection, analysis, and display.

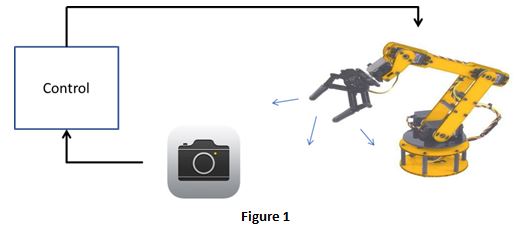

Also, consider that a Category #2 type of invention, as depicted in Figure 1 below, may relate to a classic feedback loop where sensed data collection is a tool for machine learning which results in improvement of the operation of the machine tool.

In this scenario, if the claims of the patent describe the features which lead to the improvement of the operation of the machine tool itself, there is a stronger chance of overcoming a rejection under 35 U.S.C. §101, as this should be interpreted as a patent eligible invention which as a whole improves the technological environment.

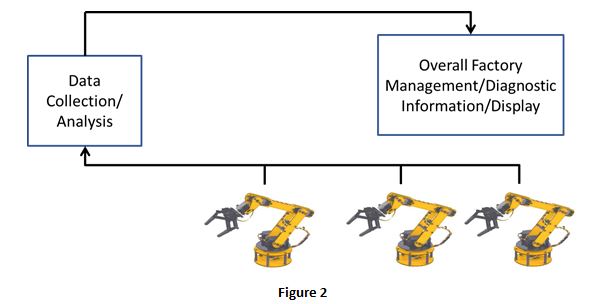

However, a more challenging scenario is presented when sensed data is used not for direct machine learning or control feedback to improve the operation of the machine or robotic equipment, but it is for some purpose related to overall factory management or to display useful information to a user, as illustrated in Figure 2 below.

The scenario of Figure 2 represents a bigger challenge if the alleged improvement is interpreted as mere data collection as opposed to a direct improvement to the technological operations of the factory. In other words, the scenario shown Figure 2 is closer to the facts of Electric Power Group or Digitech. Also, these types of innovations may be addressing a tangential problem arising from the factory environment itself such as maintenance or managing battery life of remote sensing equipment; managing machine usage to enhance long-term durability; or addressing networking/computing restraints on hardware/software that only arise from unique factory environment. In many cases, a comparable but non-feasible solution exists in a conventional computing environment, but novelty arises from tailoring to a solution to the factory setting.

The above example represents the disconnect between the language we find in precedential case law and the nature of Factory Automation inventions. For instance, if you are a company that came up with an amazing innovation in data collection that is used to train AI software, but all your commercial activities stop short of actually feeding that data to the actual AI software, then you will need to fight hard to avoid being compared to the facts of the case of Electric Power Group, and it will be challenging to show that your invention takes your collected data and “applies it” in some unique manner.

Therefore, for in-house IP Managers and patent law practitioners in the area of Factory Automation, it is important to thread the needle between getting the broadest claim scope possible in the fertile AI intellectual property landscape, while also avoiding the challenges of avoiding an abstract idea rejection.